This is Calen’s sixth post in a 13-part series, “Agile Myths and Misconceptions” where he strives to correct 12 common misconceptions about Agile Software Development.

This is my sixth post in my 13-part series, “Agile Myths and Misconceptions”, It’s based on the talk I gave at the first PSIA Softech Philippine Software Engineering Conference. I am striving to correct 12 common misconceptions about Agile Software Development.

In Kent Beck and Martin Fowler’s book, “Planning Extreme Programming”, they wrote “The Customer Bill of Rights”. One of those rights is this:

“Customers have the right to an overall plan, to know what can be accomplished when and at what cost.”

Core to the intent of Agile is to give customers predictability. It’s sad that Agile has the opposite reputation.

Agile Means Evidence-Based Decision-Making

Probably the reason why Agile has a reputation for being unpredictable is because Agile avoids making upfront estimates, requirements and design decisions, because core to its principles is evidence-based decision-making. Important decisions have to have a firm basis, to reduce or avoid risk and waste, and so decisions are deferred until such basis is obtained. That seems like common-sense, right? But most organizations want critical decisions made upfront, before enough basis for making such critical decisions have been gathered.

Evidence-Based Requirements

Have you ever heard project teams complain, “Customers don’t know what they want!” Well, why don’t we stop fighting this and just take it for a fact? For any project of significant size, your users and stakeholders will never be able to tell you what they really need or want until they have something in front of them that they can use. There’s little point in getting users and stakeholders to detail everything they think they want upfront, because as soon as they have something in front of them that they can use, they’ll realize that a lot of what they asked for was wrong. If user usage or stakeholder demos only happen at the end of a project, this will just lead to a lot of expensive change requests.

Agile and Iterative approaches advocate writing just enough requirements to get the team going. The team quickly builds a minimal product that can be used by customers or stakeholders, they get the feedback of the customers or stakeholders, and then use that feedback to modify existing requirements or to create succeeding requirements. In this approach, requirements have a reliable basis.

As the Lean Startup people like to say, “It’s not what people say, it’s what they do”. The only way to avoid a series of wasteful change requests is if you put something in front of customers or stakeholders early and often, and then consistently use the feedback derived as a basis for shaping requirements.

Full requirements upfront? That’s just creative writing.

Evidence-Based Technical Design

How many times have you heard of projects that were completed and deployed, but were too slow to be usable? This story happens too often, sometimes in spectacularly public projects such as the US government’s Healthcare.gov website.

How many times have organizations purchased very expensive technology – ESBs, databases, complex hardware, etc. – only to have them idle because there was not enough technical knowledge in the company, or the technology was not a fit for the problem being solved, or unexpected but necessary additional consulting hours or components were too expensive?

How many times has a team decided to try out a new and much-hyped technology, only to get bogged down in the middle of the project because the technology doesn’t address the project’s needs, or the learning curve was too steep?

How did these very expensive and disastrous technical decisions come about? Usually, it’s because an organization decides to make technical design decisions based only on vendor documentation, vendor demos, blog articles, user group meetings, Youtube videos…

When Agile teams are faced with a technical decision, they don’t just rely on vendor documentation or articles they find on the web. They code. Agile system design is based on Spikes. A Spike is some code that a team writes in order to shed light on an unknown. The unknown might be how long will it take to build a requirement, or the unknown could be whether a particular technology or design approach is appropriate for the business problem being solved, or is a fit for the skillset of the team.

Performance tests should be done early. When performance testing is done late in a project, a ton of code would have already been written on top of the selected technical design. When the team finds out that the technical design does not meet the performance requirements, it becomes very difficult and expensive to fix the design. Usually, the fixing process introduces a lot of bugs.

A team should build Spikes for performance testing early in the project, before a lot of investment in code has been committed. The team should select the use cases or scenarios that are most likely to occur, as well as the use cases or scenarios that the team thinks will be the likely performance bottlenecks. It should build Spikes that closely match the technology stacks that will be used in these use cases or scenarios, and then subject the Spikes to various performance tests that will simulate the kinds of stresses or loads that the stack will likely go through. A useful tool we have used for performance testing is JMeter, but I’m sure there are others out there that we haven’t tried. For additional insight, you might consider using a profiler; for Java, you can use YourKit, VisualVM or Spring Insight. Here’s a list of some other tools for performance testing or profiling.

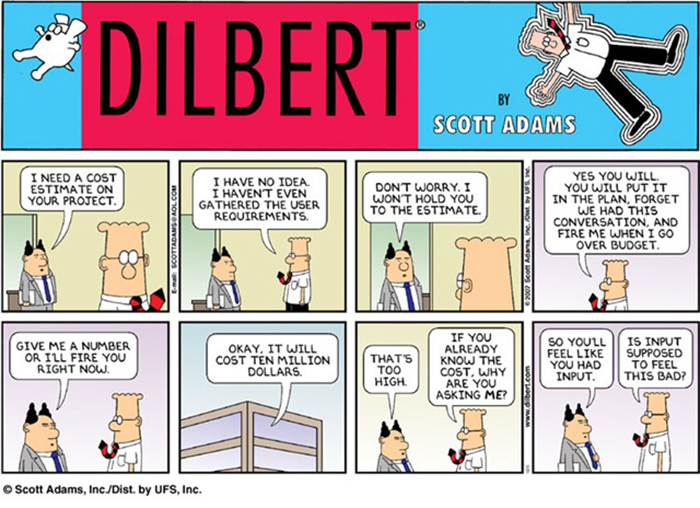

Evidence-Based Estimates

How are estimates done in fixed-scope projects? Function Point Analysis or one of its derivatives? The number of database tables multiplied by X man-days per table? We’ve all heard these before. First of all, how do you do Function Point Analysis or count database tables if much of your requirements are likely to change?

Second, how do you account for organizational factors – How long does it take for signatories to sign-off on documents? During User Acceptance Testing (UAT), do the testers submit findings to the development team early and often, or do they bunch up their findings towards the end, causing extensions of the UAT phase? Does IT operations have the process and the skills to properly and quickly deploy the application, or are the IT processes or skills usually causing delays?

Some people, after working with an organization and a codebase long enough, develop a knack for estimation. However, you put that same person in a different organization or a different codebase, and their estimations are bound to be significantly off. Good estimation only happens when the estimator has strong experience with both the codebase and the organization.

Experienced Agile teams are aware that good estimates can only be based on experience with codebase and organization. At the same time, it is in the Customer Bill of Rights that customers are entitled to accurate estimates. So how is this paradox resolved?

If the team has some experience with a similar system or organization, then they can give a wide-ranging estimate – for example, the team might say that based on previous experience, the project will take from twelve to eighteen months. If the team lacks enough experience to provide even a wide-ranging estimate with confidence, the team turns to Spikes. The Agile team should always emphasize that, at this point, these are weak estimates, and that better estimates can only be derived after a few iterations.

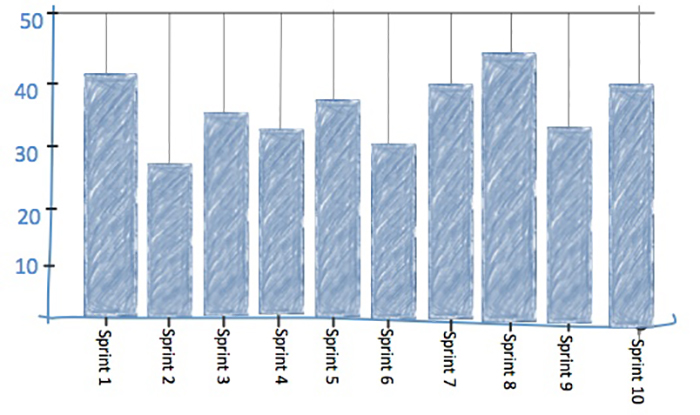

Once the team gets started, the team tracks its Velocity. As it’s velocity stabilizes, it has an idea of how much functionality it can deliver over time. The team can then give tighter estimates to the customers on when the customers can expect certain functionality.

Conclusion

Fixed-scope, upfront-design projects give an illusion of predictability, with their thick and complex documentation formats and design diagrams. But that’s all they are, illusions. They are founded very little evidence.

On the other hand, Agile requirements, design and estimates have the reputation of being unpredictable, because they cannot be given upfront. Instead, they are only provide once enough evidence for such have been gathered to be reliable. Agile requirements, design and estimates take a little more time end effort, but at least you can actually count on them.

For my next installment of this “Agile Myths & Misconceptions” series, I plan to delve a little more on the design aspect of Agile, tackling Agile Myth #6: “Agile Means No Upfront Design”.

Originally posted at: “Agile Myth #5: Agile is Unpredictable”